<<< BACK TO SPECIAL PROJECTS

|

Everyday Renaissance (After All...)

Acquired by MET: Metropolitan Museum, Thomas J. Watson Library, NYC. Scroll down for italian text and english google translation PRESS REVIEWS BELOW |

|

EVERYDAY RENAISSANCE (After All...)

Artist's Book 4 Limited edition, signed and numbered Paperback, (15x21)cm, 48 pages, color Price: 25 € (free shipping) Each copy includes an original work/intervention To buy your copy write please to: [email protected] Impressum Edizioni Inaudite | Collana Gli Irrilevanti Artist's Book 4 | BF4 - 2014 Barbara Fragogna | EVERYDAY RENAISSANCE (After All...) © February 2014 All Rights Reserved |

|

|

SENZA TITOLO CON SOTTOTITOLO

Tagliamo la testa al toro. Everyday Renaissance non ha bisogno di spiegazioni. Si capisce. E’ chiaro. Puoi interpretarlo a più livelli e dipende solo dalla chiave che hai in mano (Le donne, i cavallier, l’arme, gli amori...*). - Per chi non si accontenta: in Everyday Renaissance - After All…, IL RINASCIMENTO QUOTIDIANO - Dopo tutto…, non c’è messa in scena. Questa è la vita. La non-bellezza della banalità. E’ uno scherzo, un gioco ironico, una citazione. C’è più Pirandello che Viola, più Woolf che Sherman, più De Angelis che Modugno, più Sally che Charlie (Brown). - Per i virtuosi del Mac: gli interventi photoshop sono dei collage Wabi Sabi. Non si voleva essere precisi bensì veloci, freschi. La macchina fotografica è bassamente (biecamente?) risoluta. Mettiamo le mani avanti, conosciamo i nostri polli. Non c’è necessità di baciarle, queste mani. Upper carità (Cit. da SUBedizioni - I libri copertina). - Per i lettori mordi e fuggi: speriamo che per una volta, dato che tutto segue un ciclo, che prima o poi tutto torna e che chi la fa l’aspetti, speriamo che a breve (e facciamo finta che sia già cominciato) ritorni il desiderio di rinascita, l’inventiva, lo stimolo, l’idea, la competizione costruttiva che ha come esempio i secoli passati che a quanto pare voi italiani (ma non solo voi e a prescindere che fosse di questo o di quell’altro governo) non volete più insegnare ai vostri figli. Bravi. Bella mossa. - Per gli intellettuali di sinistra: … di cosa? *Cit. Ludovico Ariosto, incipit dall’Orlando Furioso. |

UNTITLED WITH SUBTITLE

(google translation concept for low budget projects) Let’s cut the Gordian knot. Everyday Renaissance needs no explanation. You can tell. It’s clear. You can interpret it in some different levels, it depends only on the key you have in your hand (... And one man in his time plays many parts...*). - For those who are not easily satisfied: in Everyday Renaissance ( After All ... ) there is no staging. This is life. The not-beauty of the banality. It ‘ a joke, an ironic game, a quote. There is more Pirandello than Viola, more Woolf than Sherman, more De Angelis than Modugno , more Sally than Charlie (Brown). - For the Mac experts: the photoshop interventions are Wabi Sabi collages.The goal was not to be accurate but fast and fresh. We put our hands forward, we know our chickens. There is no need to kiss, those hands. Please. - For readers that “hit and run”: we hope that for once, since everything follows a cycle, since sooner or later it all comes back and since anyone who goes around comes around, we hope that soon (and let’s pretend that it has already begun) will return the desire for rebirth, the inventiveness, the stimulus, the idea, the constructive competition that has, as its example, the past centuries education. The same education which apparently you Italians (but not only you) no longer want to teach to your children. Bravo. Nice move. - For the left wing intellectuals: ... what wing? *Quote W. Shakespeare, As You Like It. |

Text by Aline Vater published on Kwerfeldein (18.3.2014)

|

Everyday Renaissance (After All..):

Selbstbildnisse, die Dürer, Botticelli und Leonardo einen Herzinfakt beschert hätten. Die in Italien geborene vielseitige Künstlerin Barbara Fragogna rezipiert kollektive Wahrheiten über Schönheit und Verfall, diskutiert stereotype, historisch geprägte Geschlechterrollen und transzendiert diese spielerisch-charmant mit Mitteln der Ironie. Eine Vorstellung des Kunstbuchs „Everyday Renaissance (After All…). „Als ich klein war, bat mich meine Großmutter immer, nicht mit Jungs zu gehen, Jesus zu lieben und ein gutes Mädchen zu sein. Ich wuchs mit zwei Vorstellungen von Frauen auf: der Jungfrau und der Hure.“ Dies ist ein Zitat der Pop-Ikone Madonna, die in einer Zeit geboren wurde, in der Frauen entweder Heilige oder Huren waren (1). Insbesondere in den 70er Jahren entlarvten Künstlerinnen diese traditionelle Rollenzuschreibungen als soziokulturelle Klischees (z.B. Ana Mendieta, Judy Chicago, Martha Rosler, Nancy Spero, Hannah Wilke, Guerilla Girls). Trotz dem immensen Fortschritt der Gleichberechtigung von Frauen gibt es auch heute noch Unterschiede zwischen den Geschlechtern, die sich in marktorientierten Schönheitsdogmen, klischeehaften Rollenzuweisungen und unterschiedlichen Entwicklungschancen im Berufsleben widerspiegeln. Dies zeichnet sich insbesondere im Kunstmarkt ab, der Künstlerinnen weitestgehend ignoriert. Laut einer statistischen Analyse sind weniger als 25% der von Galerien vertretenen Künstler Frauen (2). Erst seit wenigen Jahren sind im „Kunstkompass“ drei Frauen in die Top-Ten Rangliste der KünstlerInnen vertreten (Rosemarie Trockel, Cindy Sherman und Pipilotti Rist), deren „Marktwert“ weit hinter dem von Gerhard Richter und Bruce Nauman rangiert. Neben Cindy Sherman, Bettina Rheims oder Marina Abramovic gibt es derzeit eine Generation aktiv wirkender Künstlerinnen, die sich mit diesen soziokulturellen Konstrukten beschäftigen. So auch die derzeit in Berlin lebende italienische Künstlerin Barbara Fragogna, die in „Everyday Rennaisance“ durch einen selbstbewusst-spielerischen Umgang klischeehafte traditionelle Menschenbilder entlarvt und über das mutige Mittel der Selbstironie zum Schmunzeln verführt. Barbara Fragogna ist eine multidisziplinäre Künstlerin, die sich neben Malerei, Installationen, kuratorischer Tätigkeit und Grafik auch mit Fotografie beschäftigt. In ihren Arbeiten diskutiert sie häufig Widersprüche psychologischer und soziologischer Konstruktionen, in dem sie diese ohne Scham und Reue enthüllt, zerteilt und versöhnt. In diesem Sinne besteht das Konzept hinter „Everyday Renaissance“ aus einer Gegenüberstellung eines populären Renaissancegemäldes und einem äquivalenten Selbstportrait, mit dessen Hilfe die Künstlerin auf klassische Darstellungsweisen der Kunstgeschichte referiert und sie in einen neuen Zusammenhang stellt. Die Interpretation der Bilder ist, wie Barbara Fragogna beschreibt, intuitiv und von individuellen Erfahrungen abhängig: „You can tell. It´s clear. You can interpret it on some different levels, it depends only on the key that you have in your hand” (deutsch: Man erkennt den Sinn. Er ist klar. Du kannst es auf unterschiedlichen Ebenen interpretieren, es hängt nur von dem Schlüssel ab, den du in deiner Hand trägst). Daher ist “Everyday Renaissance” einem breiten Publikum von Personen zugänglich, die sich mehr oder weniger (und nicht notwendigerweise) intensiv mit Kunstgeschichte beschäftigt haben. Nicht das Wort führt zu Erkenntnis, sondern die Imagination – das ist das Dogma, dass Barbara Fragogna umtreibt. Die Wahl der Epoche der Renaissance ist keineswegs zufällig. Die Renaissance (15./16.Jh) ist eine der bedeutsamsten Kunstepochen, in der Künstler wie Leonardo und Michelangelo, Raffael und Tizian, Dürer und Holbein nach höchster künstlerischer Vollkommenheit, Schönheit und Harmonie strebten. Durch die Auseinandersetzung mit wissenschaftlichen Erkenntnissen wandelte sich das Verständnis von Perspektive und Anatomie in der Kunst und verhalf Kulturschaffenden zu nie dagewesenem Ansehen (3). Zum ersten Mal nahmen Künstler einen ehrenwerten Platz unter den bedeutenden Figuren des Zeitalters ein, sie wurden hofiert von Päpsten und Kaisern, die miteinander wetteiferten, ihre Kunstwerke zu besitzen (3). Nicht zufällig werden diese Werke der Renaissance neuzeitlichen Selbstportraits entgegengesetzt – in einer Zeit, in der der Kapitalismus den Kunstmarkt beherrscht und nur noch ein verschwindend geringer Bruchteil von KünstlerInnen von Sammlern und Museen hofiert werden. Im Sinne einer kapitalistischen Marktorientierung ist auch die Auswahl des künstlerischen Mittels in Barbara Fragogna´s Selbstportraits einzuordnen. Die Künstlerin nutzt für ihre Darstellung in „Everyday Renaissance“ eine wabi-sabi ähnliche Fülltechnik zur Betonung von Inhalt, die photoshop-verwöhnte Augen unter Umständen flirren lassen. Die Wahl dieses Mittels liegt jedoch nicht in der Unfähigkeit der Anwendung von Photoshop-Kenntnissen der Künstlerin begründet, sondern ist ein bewusst gewähltes Werkzeug, um dem Inhalt Vorrang vor qualitativen Kriterien zu schenken. Das Ziel des Einsatzes von Bildbearbeitung ist es nicht, akkurat, sondern schnell und zeitgemäß zu sein. In diesem Sinne ist „Everyday Renaissance“ ein hervorragendes Beispiel zur Überwindung komplexer Sachverhalte durch unkonventionelle Methoden. Barbara Fragogna bezeichnet dies als „die Schönheit des Banalen“, in dem die Technik zu einem Witz, zu einem ironischen Spiel, zu einem Zitat utilisiert wird. Durch die Auswahl dieser Technik wird nicht nur das Konzept von Schönheit in der Kunst, sondern auch die wachsende Flut perfekter, photoshop-dressierter Bilder kritisch adressiert. Was haben diese Gegenüberstellungen nun mit einer ironischen Hinterfragung von Rollenbildern zu tun? Um dies zu verdeutlichen, werden im folgenden Artikel stellvertretend 6 der 22 Selbstportraits aus dem Katalog „Everyday Renaissance“ herangezogen. Mit dem Ende des Mittelalters begann das Zeitalter der Renaissance, eine Zeit der „Wiedergeburt“ der antiken Kultur. Obgleich sich der Mensch von traditionellen Werten der Kirche langsam löste, und Werte wie Freiheit, Gleichheit und Selbstverwirklichung an Bedeutung gewannen, wirkte sich dieser Fortschritt kaum auf die weibliche Bevölkerung aus (ausgenommen auf den weiblichen Adel). Die Mehrzahl der Künstler war männlichen Geschlechts, einer der bekanntesten deutschen Renaissancekünstler ist Albrecht Dürer. Barbara Fragogna nutzt ein Selbstportrait von Dürer, in dem er eine Haltung hierarchischer Frontalität einnimmt, die normalerweise malerischen Bildnissen von Königen und christlichen Figuren vorbehalten blieb. Dürer stellt sich in diesem Portrait mit Gott gleich. Fragogna nutzt diese Haltung und inszeniert sich mit einem weißen Schnurbart aus Creme, die durch eine Nassrasur unschöne (d.h. unweibliche) Oberlippenhaare entfernen soll. Eine graue Stoffkutte wird symbolträchtig der Schönheit von Dürers Haarpracht entgegengesetzt und camoufliert die ursprünglichen weiblichen Züge der jesus-ähnlichen Figur. Barbara Fragogna, After Dürer, Self-portrait shaving mustache with a not proper cream.

Links: Albrecht Dürer, Self-portrait with fur, 1500, Alte Pinakothek, Munich. In einer weiteren Arbeit mimt Barbara Fragogna ein Christusportrait von Memling nach, der dem Betrachter durch eine Handbewegung seinen Segen gibt. Bedeutsam ist das Fehlen heiliger Insignien (z.B. einem Kreuz) bei Memling. Dieses Fehlen von Insignien greift Fragogna in ihrer Version auf und ersetzt an deren Stelle eine Zahnbürste, um die Pflege des eigenen Körpers segensgleich zu inszenieren. Der Schaum am Mund erinnert an ein tollwütiges Katzentier, das den obsessiven Umgang mit Körperpflege metaphorisiert. Barbara Fragogna, After Memling, Self-portrait brushing teeth.

Links: Hans Memling, Christ Giving His Blessing, 1478. Norton Simon Museum, Pasadena, CA, USA In einem weiteren Selbstportrait wird das “Schweißtuch der Veronika” (Sudarium) ironisch umgedeutet. Das Schweißtuch der Veronika war einst die kostbarste Reliquie der Christenheit und befindet sich heute in einem gewaltigen Tresor im Petersdom in Rom. Nach der christlichen Überlieferung hat Veronika Jesus von Nazareth ein Stofftuch gereicht, damit sich dieser Schweiß und Blut vom Gesicht abwaschen konnte. Dabei soll sich das Gesicht von Jesus auf wunderbare Weise auf dem Sudarium eingeprägt haben. Fragogna inszeniert sich komplementär als christusgleiche Figur beim Färben der vormals ergrauten Haare. Auf einem Handtuch erscheint nicht ihr Gesicht, sondern das von Jesus – eine ironische Art, um mit der Rolle der Frau im Christentum zu operieren. Links: Barbara Fragogna, After The Master, Self-portrait dyeing hair and finding out what’s coming next.

Rechts: St. Veronica with the Sudarium by Master of the Legend of St Ursula, 1480-1500, Private Collection. In einem weiteren Selbstportrait nimmt sie ein Gemälde von Dieric Bouts ironisch unter die Lupe. Bouts sah seine Aufgabe darin, das Schöne der weiblichen Vollkommenheit, hier der von Maria, auszudrücken. Die Nacktheit von Maria stand für Unschuld und verdeutlicht die mütterlich umsorgende Rolle, die Frauen in der damaligen und der heutigen Zeit zugeschrieben wird. Fragogna schlüpft in die Rolle der Maria und negiert die ihr zugeschriebene Mutterrolle durch den Versuch der dauerhaften Reduktion unerwünschter Körperhaare. Hier geht es weniger um Selbsterfoschung als um die Infragestellung gesellschaftlicher Rollen. Diese Gegenüberstellung konträrer Auffassungen von Lebensentwürfen gibt der Serie eine verstörend authentische Qualität. Zugleich macht sie das Ganze zu einem komplexen Vexierspiel: So klar und prägnant, wie die Botschaft auf einen ersten gewagten Blick scheint, umso inhaltsreicher wird sie, wenn man die einzelnen historischen Puzzlestücke in ihrer Gesamtschau betrachtet. Rechts: Barbara Fragogna, After Bouts, Self-portrait unrooting those ugly, annoying, nasty hair on the breast.

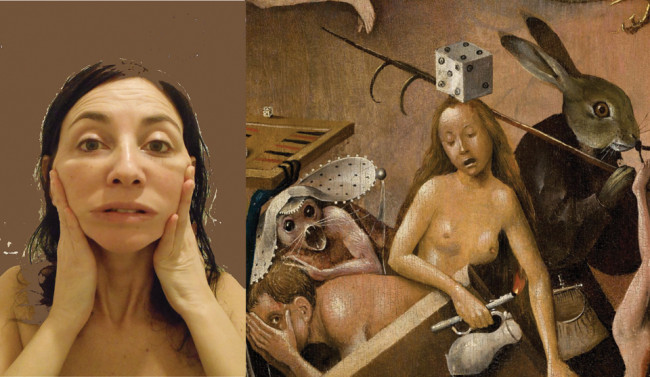

Links: Dieric Bouts, Virgin and Child, last quarter of 15th century, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Diese oben erwähnten Arbeiten stehen einem bekannten Triyptichon von Hieronymous Bosch und dessen Uminterpretation von Fragogna kontraintuitiv entgegen. Hieronymous Bosch war ein niederländischer Maler, der vertraut war mit der Vielfalt wissenschaftlicher Erkenntnisse seiner Zeit. Kein Maler dieser Periode stand dem Geist der italienischen Renaissance ferner als Bosch, der nicht die Schönheit, sondern vor allem die moralischen Schwächen der Menschheit abbildete. Nicht zufällig, sondern ganz bewusst wählt Fragogna Boschs Gemälde aus, um das Gesamtkonzept von „Everyday Renaissance“ zu komplettieren. Nicht zufällig existieren inhaltliche Parallelen zwischen Fragogna´s frühen Werken und denen von Hieronymus Bosch (s.h. Gemälde von Barbara Fragogna aus den Jahren 2004-2007). Boschs Bildwelten lassen die Symbolik des Mittelalters hinter sich und integrieren dämonische Wesen, die düstere Visionen abbilden. Barbara Fragogna nutzt einen Ausschnitt des linken Flügels des bekannten Triptychons „Der Garten der Lüste“ von Bosch, dass häufig die „musikalische Hölle“ genannt wird. Die Bezeichnung „musikalische Hölle“ rührt daher, dass ein deutlicher Schwerpunkt auf dem Einsatz von Musikinstrumenten als Folterwerkzeug liegt. Das Detail, das Fragogna auswählt, stellt eine Frau mit einem Würfel auf dem Kopf dar, das als Warnung vor dem Einfluss der Frau (vermeintlich die Figur der Eva) fungiert, die den Mann (Adam) zur Sünde verführt hat (4). Im Original malträtiert ein Dämon einen vor einem Spieltisch liegenden Mann zweierlei durch Würgen und durch Erdolchen. Der Dämon trägt ein Schild auf dem Rücken, auf dem eine abgeschnittene und aufgepießte Hand erkennbar ist, eine Prozedur, die im Mittelalter häufig als Strafe bei Falschspiel oder Diebstahl vollzogen wurde. Der Würfel auf dem Kopf der Figur wird in einigen Abhandlungen als Symbol der weiblichen Verführerrolle zum Falschspiel des vor ihr liegenden Mannes gedeutet. Die Symbolik des unwillkürlichen Zerteilens körperlicher Segmente kopiert Barbara Fragogna in ihrem Selbstportrait, das für das Erschrecken der Erkenntnis des „Auseinanderfallens“ von Schönheit steht. Links: Barbara Fragogna, After Bosch, Self-portrait finding out that I am falling apart.

Rechts: Hieronymous Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights (detail), between 1490 and 1510. Museo del Prado, Madrid. Der Erhalt der weiblichen Schönheit wird auch in einem weiteren Selbstportrait thematisiert. Hier kooperiert Fragogna mit „der hässlichen Herzogin“, einem von Quentin Metsys‘ am häufigsten rezipierten Gemälde. Die hässliche (von Gesichtszügen her vermännlichte) Herzogin stellt eine groteske alte Frau dar, die in dem ursprünglichen Gemälde eine minimalistische rote Blume in der Hand hält. Diese Blume symbolisiert den vermeintlich erfolglosen Versuch der Attraktion männlicher Bewerber. Indem Barbara Fragogna die Blume durch einen Porenreinigungsstreifen austauscht, macht sie die hässliche Herzogin zur Komplizin zum Erhalt von Schönheit. VerLinks: Barbara Fragogna, After Metsys, Self-portrait dyeing hair (yes, again) and rooting black spots out of the nose (with the precious help of Her Majesty the Duchess).

Rechts: Quentin Metsys, The Ugly Duchess (also known as A Grotesque Old Woman), 1513. National Gallery, London. Durch diese Interaktion der beiden Figuren wird deutlich, dass das Konzept von „Everyday Renaissance“ vor allem durch die Gegenüberstellungen funktioniert. Bei den Diptychen handelt es sich jedoch nicht um individuelle Selbstanalysen, denn Gesicht und Körper werden als Instrumente zum Transport einer Botschaft und als Erkundungsmoment von Identität eingesetzt, indem sie kollektive Wahrheiten der Bedeutung von Schönheit und Verfall rezipieren. Bilder prägen unsere Sicht auf die Welt und letztlich auch, wie wir uns selbst sehen. Barbara Fragognas Maskeraden sind mutig, denn sie stellen mittels einer unverfälschten Wiedergabe eigener körperlicher Merkmale bzw. Defizite eine unvermittelte Befragung des Betrachters dar, die dem Modell nichts lässt, hinter dem es sich verstecken könnte. Die Künstlerin sucht diese Auseinandersetzung und macht sich gleichermaßen Ernst und Ironie zu eigen, um ihre Botschaft zu vermitteln. Ihre Arbeit erzählt davon, wie man Schmerz erträgt, umwandelt und sich von ihm befreit. Die Künstlerin fungiert damit als eine Art Spiegel, indem sie schmerzvolle Gefühle ironisch transzendiert. Wir leben immer noch in einer Zeit, in der physische Schönheit ein objektives Kriterium für gesellschaftliche Akzeptanz darstellt. Es ist auch eine Zeit, in der Frauen wählen müssen, ob sie Mutter, Geliebte oder Künstlerin sein wollen. Um es mit den Worten von Marina Abramovic auszudrücken: „Before you start to be an artist, you have to be sure that this is what you want. And then you have to be ready to sacrifice everything and be ready to be alone. It's not easy life, but when you succeed with your ideas, reward is wonderful.” (deutsch: “Bevor man Künstlerin wird, muss man sich sicher sein, dass es das ist, was man will. Und dann muss man bereit sein, alles zu opfern und allein zu sein. Das ist kein einfaches Leben, aber wenn man es schafft, seine Ideen umzusetzen, ist die Belohnung wundervoll.“) Kwerfeldein Leser, die neugierig auf die restlichen 16 Selbstportraits geworden sind, können eines der Exemplare des Kunstbuchs “Everyday Renaissance” erwerben (limitierte, signierte und nummerierte Auflage von 250, Kontakt: [email protected]), das im Edizione Inaudit erschienen ist (http://sinedieproject.weebly.com/everyday-renaissance.html). Wer zusätzlich gern in direkten Austausch mit Barbara Fragogna treten möchte, ist eingeladen die Ausstellung „Everyday Renaissance“ in der Galerie 52 in 12045 Berlin zu besuchen. Die Vernissage findet am 22. März 2014 unter Anwesenheit der Künstlerin statt. Die Ausstellung ist bis zum 5. April 2014 zu besichtigen. Quellen und Literatur 1 Schoppmann, W. & Wipplinger, H.-P. (2010). Lebenslust und Totentanz. Olbricht Collection. Wien: KunstHalle Krems. 2 Pora, R. & Seiferlein, L. Frauen vorn. Stars und Newcomer, Überflieger und Vorreiterinnen. In Art Magazine, Nr 11/2013 von Nov. 2013, S. 20-29. 3 Gombrich, E. H. (1972). Die Geschichte der Kunst. Zürich: Belser Verlag Stuttgard. 4 Honour, H. & Fleming, J. (1992). Weltgeschichte der Kunst. München: Prestel Verlag. |

Everyday Renaissance (After All…) :

Self-portraits which would have given Dürer, Botticelli and Leonardo a heart attack. The Italian multi-skilled artist Barbara Fragogna challenges collective truths about beauty and decay, discusses stereotypical, historically established gender roles and transcends those playful-charmingly with means of irony. An introduction of the artist book "Everyday Renaissance (After All ...). "When I was little, my grandmother always told me not to go with guys, to love Jesus and be a good girl. I grew up with two images of women: the virgin and the whore". This is a quote of pop icon Madonna, who was born in a time when women were either saints or whores (1). Especially in the 70s female artists unmasked those traditional roles as sociocultural stereotypes (eg. Ana Mendieta, Judy Chicago, Martha Rosler, Nancy Spero, Hannah Wilke, Guerilla Girls). Despite of an ongoing progress of striving for womens rights, there are still differences between the sexes, which are reflected in market-oriented beauty dogmas, clichéd role assignments and different development opportunities in professional life. This is particularly reflected in the art market, where female artists are still largely ignored. According to a statistical analysis, only about 25 % of the artists represented by galleries are women (2). Only in recent years three female artists risen to the top ten list of the world-wide "Art Compass" (Rosemarie Trockel, Cindy Sherman and Pipilotti Rist), however, their "ranked market value" is far beyond those of Gerhard Richter and Bruce Nauman. In addition to Cindy Sherman, Bettina Rheims or Marina Abramovic, a generation of female artists deal with these sociocultural constructs. Along with those, the Italian artist Barbara Fragogna exposes clichéd traditional images of women and seduces the observer with courageous means of self-ironic playful manners in her series “Everyday Renaissance”. Barbara Fragogna is a multidisciplinary artist who works with painting, installation, curatorial activities and graphic design, but also with photography. In her works she often discusses contradictions of psychological and sociological constructions by revealing, defragmenting and reconciling them without shame and remorse. Similarly, the concept behind "Everyday Renaissance" consists of a juxtaposition of a popular Renaissance paintings and an equivalent self-portrait. By doing so, the artist refers to classical representations of femininity in art history and places them into a new context. The interpretation of Barbara Fragognas images is rather intuitive and depends on individual experiences: "You can tell. It's clear. You can interpret it in some different levels, it depends only on the key did you have in your hand". In this sense, "Everyday Renaissance" is available to a wide audience which not necessarily needs to have knowledge in art history. Not the word leads to knowledge but imagination - this is the dogma of Barbara Fragogna. The choice of the Renaissance paintings is by no means accidental. The Renaissance (15/16th century) is one of the most important periods in art history, in which artists such as Leonardo and Michelangelo, Raphael and Titian, Dürer and Holbein performed the highest artistic perfection, beauty and desired harmony. The examination of scientific findings changed the understanding of perspective and anatomy in the arts and helped the cultural sector to an unprecedented prestige (3). For the first time, artists took an honorable place among the major figures of their century; they were courted by popes and emperors, who competed with each other to own a precious artwork. Not coincidentally, these works of the Renaissance are opposed to modern self-portraits - in a time when capitalism dominates the art market and only a tiny fraction of artists are being supported by collectors and museums. This background of a current capitalistic orientation of the art market classifies the choice of Barbara Fragognas artistic means. The artist uses a "wabi sabi" like filling technique for emphasizing content in "Everyday Renaissance", which may initially irritate Photoshop used eyes. The choice of this remedy does not lie in the inability of the use of Photoshop skills of the artist, but is a deliberately chosen tool to emphasize content that takes precedence over qualitative criteria. The objective of the use of this image processing tool is not to be accurate, but fast and fresh. In this sense, "Everyday Renaissance" is an excellent example of overcoming complex issues through unconventional methods. Barbara Fragogna refers to this as "the beauty of the banal" in which the technique is utilized as a joke, an ironic play and a quote. By selecting this technique, not only the concept of beauty in art, but also the growing tide of perfect, Photoshop-designed images is critically addressed. How do these comparisons ironically question gender roles? To illustrate this, 6 of the 22 self-portraits are representatively chosen from the catalog "Everyday Renaissance" in the following. With the end of the Middle Ages, the Renaissance started, a time of "rebirth" of ancient culture. Although traditional values of the church broke slowly, and human beings gained values such as freedom, equality and self-realization, this progress had hardly any effect on the female population (excluding the female nobility). The majority of the artists were male. One of the most famous German Renaissance artists is Albrecht Dürer. Barbara Fragogna uses a self-portrait of Dürer, in which he takes a hierarchical frontal perspective, which normally remained reserved to picturesque portraits of kings and Christian figures. In this portrait, Dürer arises equally with God. Fragogna uses this approach and presents herself with a white mustache of cream, which is removes unsightly (unfeminine) upper lip hair through wet shaving. A gray fabric cowl contrasts Dürers beautiful hair and camouflages the original female traits of the Jesus-like figure. Rechts: Barbara Fragogna, After Dürer, Self-portrait shaving mustache with a not proper cream.

Links: Albrecht Dürer, Self-portrait with fur, 1500, Alte Pinakothek, Munich. In a further work, Barbara Fragogna mimes a Christ portrait of Memling who gives his blessing by a hand movement. The absence of the sacred symbols (eg. a cross) is significant in Memlings painting. Instead of a holy blessing, Fragogna holds a toothbrush in her hand. The foam on her mouth represents a rabid animal and is metaphorically used to criticize an obsessive use of body care. Rechts: Barbara Fragogna, After Memling, Self-portrait brushing teeth.

Links: Hans Memling, Christ Giving His Blessing, 1478. Norton Simon Museum, Pasadena, CA, USA I another self-portrait, the "Veil of Veronica" (Sudarium) is ironically reinterpreted. The Veil of Veronica was once the most precious relic of Christianity and is now stored in a huge vault in St. Peter's Basilica in Rome. According to Christian tradition, Veronica has passed Jesus of Nazareth a cloth to wash away sweat and blood from his face. Here, the image of Jesus is said to be miraculously imprinted on the handkerchief. Fragogna presents herself when coloring grey hair. In her version, the face of Jesus appears on the handkerchief instead of her face – an ironic way to operate with the role of women in Christianity. Rechts: Barbara Fragogna, After The Master, Self-portrait dyeing hair and finding out what´s coming next.

Links: St. Veronica with the Sudarium by Master of the Legend of St Ursula, 1480-1500, Private Collection. In another self-portrait she takes a painting by Dieric Bouts ironically under the microscope. Bouts has endeavored to express the beauty of female perfection, here that one of Maria. The nakedness of Maria stands for innocence and illustrates the maternal caring role that is assigned to women. Fragogna takes on the role of Mary and negates her ascribed role of following motherhood by reducing unwanted body hair. This goes beyond self-research as she rather questions social gender role assignments. This juxtaposition of contrasting established conceptions of life plans is a disturbingly authentic quality of the series. At the same time it transforms the whole subject into a complex game of deception: So clear and concise as the message seems to be on a first daring look, the more content-rich it is, if you combine the historical puzzle pieces on a broader level. Rechts: Barbara Fragogna, After Bouts, Self-portrait unrooting those ugly, annoying, nasty hair on the breast.

Links: Dieric Bouts, Virgin and Child, last quarter of 15th century, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. These works mentioned above preclude a known Triyptichon of Hieronymous Bosch and its reinterpretation of Fragogna. Hieronymous Bosch was a Dutch painter who was familiar with the diversity of scientific knowledge of his time. No painter of this period more brutally contrasted the spirit of the Italian Renaissance than Bosch, who didn´t portray beauty, but specifically the moral weaknesses of mankind. Fragogna does not choose Boschs painting by chance, but consciously uses it to complete the whole concept of "Everyday Renaissance". Not coincidentally, there are substantive parallels between Fragogna's early works and those of Hieronymus Bosch (see paintings by Barbara Fragogna from the years 2004-2007). Boschs imagery leaves the symbolism of the Middle Ages behind and integrates demonic entities that represent gloomy visions. Barbara uses a detail of the left wing of the triptych known "The Garden of Earthly Delights" by Bosch that is often called "musical hell." The term "musical hell" stems from the fact that musical instruments were used as torture devices. The detail that Fragogna selects depicts a woman with a cube on her head, as warning that the seduction of the woman (supposedly the figure of Eve) is dangerous, as she forced her husband (Adam) to sin (4). In the original version by Bosch, a demon maltreats a man in two ways by choking and stabbing him. The demon is wearing a shield with a cut hand on his back which is representative of a false play. Cutting off the right hand was often performed as punishment for cheating or theft in the Middle Ages. The cube on the head of the figure is often interpreted as symbol of the seducing role of women in advising her husband to cheat. Barbara Fragogna copied the symbolism of involuntary fragmenting physical segments and pictures the scared look as recognizing herself "falling apart". Links: Barbara Fragogna, After Bosch, Self-portrait finding out that I am falling apart.

Rechts: Hieronymous Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights (detail), between 1490 and 1510. Museo del Prado, Madrid. The preservation of female beauty is also addressed in another self-portrait. Here Fragogna cooperates with the "Ugly Duchess", one of Metsys ' most commonly-cited paintings. In the original painting, the ugly duchess is a grotesque old (male looking) woman who holds a minimalistic red flower in her hand. The flower symbolizes the (allegedly failed) attempt to attract male applicants. Fragogna exchanged the flower with a white cleansing stripe; this movement makes the ugly Duchess an accomplice in preserving female beauty. Links: Barbara Fragogna, After Metsys, Self-portrait dyeing hair (yes, again) and rooting black spots out of the nose (with the precious help of Her Majesty the Duchess).

Rechts: Quentin Metsys, The Ugly Duchess (also known as A Grotesque Old Woman), 1513. National Gallery, London. By recognizing the interaction between the two figures, it is clear that the concept of "Everyday Renaissance" works primarily through juxtapositions. The diptychs, however, are not about an individual self-analysis. Instead, the face and the body are used as a tool for conveying a broader message and exploring of identity by reciting collective truths on the importance of beauty and decay. Images shape our view of the world and, ultimately, how we see ourselves. Barbara Fragognas masquerades are brave as they provide means of purest reproductions of physical characteristics or deficits without hiding behind a mask. Barbara Fragogna simultaneously occupies seriousness and irony to convey her message. Her works tell stories on how one may endure pain, and how to transform and free oneself from him. The artist thus acts as a mirror, by transcending painful feelings with means of self-irony. We still live in a time in which physical beauty is an objective criterion for acceptance in society. This is also a time where women have to choose whether they want to be mother, a lover or an artist. To put it in the words of Marina Abramovic : "Before you start to be an artist , you have to be sure that this is what you want. And then you have to be ready to sacrifice everything and be ready to be alone. It's not easy life, but when you succeed with your ideas, the reward is wonderful." Kwerfeldein readers who are curious to see the remaining 16 self-portraits may order one copy of the artist book "Everyday Renaissance" (limited, signed and numbered edition of 250 copies, published in Edizioni Inaudite: http://sinedieproject.weebly.com/everyday-renaissance.html) by the artist on request ([email protected] or [email protected]). The ones who would like to get in touch with Barbara Fragogna are invited to visit the exhibition "Everyday Renaissance (After All…)" in the gallery 52 in 12045 Berlin. The Vernissage will take place on March the 22nd 2014 and the artist will be present. The exhibition can be visited till April the 5th. ALINE VATER Sie hat am interdisziplinären Exzellenzcluster „Languages of Emotion“ an der FU Berlin über Narzissmus geforscht und ist derzeit als Post-Doc und Psychotherapeutin (in Ausbildung) tätig. Sie hat an der Fotoschule IMAGO eine Ein-Jahres-Ausbildung absolviert und fotografiert lieber analog als digital. An der Fotografie fasziniert sie die Möglichkeit, psychologische Phänomene mit visuellen Mitteln zu erkunden, die der Sprache nicht zugänglich sind. |

EDIZIONI INAUDITE. IL LIBRO OLTRE

di Francesca Coppola

Articolo apparso parzialmente su Exibart

L’idea di Edizioni Inaudite venne a Barbara Fragogna, artista veneta trapiantata a Berlino, ma dallo spirito mobile e itinerante, mentre stava lavorando al suo progetto Nest of Dust.

Ma iniziamo dai promordi. Cioè dalla A di Artista. Perché se ogni casa editrice incarna il suo editore, è lo sviluppo coerente della sua personalità, è la sua valigia di sogni, la sua propaggine di carta, di Barbara Fragogona non si può non parlare. Considerata la sua suscettibilità rispetto al “definire” – agli “inscatolamenti di misura standard” ai telai premontati della verbosità critica, a un sistema dell’arte che pensa sempre più di frequente ai grandi numeri, a diventare un insieme parallelo a quello Hollywoodiano –, la introduco dicendo solo che è stata curatrice al Tacheles e che appartiene a quella frangia di artisti senza vessillo, assolutamente solipsisti ed autarchici ma paradossalmente, proprio in virtù di questa sorta di ostracismo creativo, uniti tra di loro da un forte spirito di comunità e di collaborazione. Fornisco al lettore un assaggio d’artista trascrivendo in parte uno dei suoi lavori, 3rd Millennium Phenomena (cover letters) Work in progress:

«Dear Gallerist, Dearest Art Critic,

I am a female artist.

I’m a lesbian.

I have a “Social-Monarchic” attitude.

[…]

I criticize all and everything, I’ve always good issues to enucleate but I do it in an approximate way (for God’s sake, You can not expect me to be ALL-specific) and afterwards I go to bed with the enemies in order to overmaster them by my passive-aggressive manipulative strategy. […]»

Per il lavoro completo: http://barbarafragogna.weebly.com/3rd-millennium-phenomena-cover-letters.html

Per tutte le altre sue opere:http://barbarafragogna.weebly.com

Dopo questo minuscolo ritratto di Barbara Fragogna si può ora passare direttamente al progetto Edizioni Inaudite.

Il nome “Edizioni Inaudite”, riuscitissimo e accattivante, come peraltro i nomi interni delle collane da Gli Irrilevanti a Big stuff, richiama quello dell’Einaudi, caposaldo dell’Editoria italiana nel cui catalogo «ciascuno vorrebbe comparire», ma dal quale la Fragogna si distanzia per avviare un progetto totalmente inaudito, per dare voce a voci marginali, inascoltate, amiche. Altro riferimento indiscusso è Virgina Woolf: «… se si vuole fare qualcosa bisogna cercare sempre di essere autonomi. Se Virginia Woolf non avesse aperto la Hogarth Press (col marito) probabilmente non avrebbe pubblicato tutti i suoi romanzi in "tempo reale" cioè in vita... attraverso quella casa editrice, dove lei, il marito e un solo collaboratore (!) , componevano le pagine (altro che inDesign!), rilegavano e distribuivano i libri, oltre ai suoi lavori ha anche permesso ad altri scrittori e intellettuali del tempo di realizzare le proprie opere. Virginia è una delle mie pietre miliari».

Se autogestirsi è il primo obiettivo dell’artista contemporaneo, oggi diventa necessario anche mantenere caratteristiche di flessibilità e di adattabilità. E un artista che è nello stesso tempo un curatore lo sa bene. Come imprescindibile è dare voce e spazio ai propri lavori e agli artisti che condividono il medesimo percorso.

Cosa può garantire insieme l’autonomia, la flessibilità e la visibilità? Il libro d’artista. «La Casa Editrice assolve così la funzione di galleria, diventa un modo per sostenere gli artisti. Diventa cioè un progetto artistico e curatoriale».

E l’occasione nasce, come accennato all’inizio, da un personale progetto di Barbara Fragogna Nest of Dust. Il lavoro, che analizza, smitizza, ironizza, l’arte concettuale per diventare un “consapevole” lavoro di arte concettuale che a sua volta tautologicamente ironizza su se stesso, contiene già in nuce la poetica della casa editrice, come quando ad esempio evidenzia la possibilità, mediante la pubblicazione, di illuminare quei lavori che spesso per ragioni di mercato restano nelle cantine degli artisti:

«esiste un’altra faccia delle molteplici Fragogna che invece darebbe ragione ai più o meno alcuni che la chiamassero “un artista di concetto”, una teorica, una Kosuthiana. Una faccia meno nota, un lato rimasto fino ad ora in ombra, una porzione di buio che in questo libercolo noi vorremmo finalmente portare alla luce».

E in un certo senso il concetto di nido come esposto dalla Fragogna costituisce le fondamenta della Casa Editrice: «un bilancio di attrazioni e repulsioni che equilibra il senso. L’allegoria degli equilibri sociali, politici, relazionali, un passo a due e un ballo di gruppo. Nel nido si viene generati e dal nido si deve spiccare il volo. La partenza e l’arrivo, il transito, il passaggio».

La casa editrice è come un nido che protegge ed è una sorta di incubatrice energetica per gli artisti. E da cosa è costituito questo nido? Su cosa possono fare affidamento gli artisti che vi si rivolgono? Estro, contaminazione, apertura, ambizione, ironia, eleganza, serietà se vogliamo parlare dei contenuti; per ciò che concerne invece gli aspetti tecnici: un’edizione numerata, firmata, con ristampe diverse dalla prima edizione ma sempre a tiratura limitata, bassi costi di produzione, un sistema di prevendita, una percentuale più alta di quella normalmente destinata agli autori a favore degli artisti, la presentazione del libro. «Diffondere una cultura del collezionismo d’arte affrancato dall’aurea altisonante e preclusa ai più che solitamente vi si associa. Le opere pubblicate e curate da Edizioni Inaudite sono per lo più libri d’artista, dunque unici, in tiratura limitata e personalizzati in ogni esemplare, quindi vere e proprie opere d’arte». È come se il libro utilizzasse l’opera per superarla, andare oltre, per farle raggiungere un nuovo confine e guadagnarsi una nuova identità.

Così all’interno della prima collana hanno trovato posto oltre alla Fragogna: Pedro Ahner e Exilentia Exiff e presto la collana Big stuff ospiterà un volume dedicato a Giosetta Fioroni e uno a Martin Reiter.

L’ultima novità però, di prossima presentazione in Italia è il volume di Barbara Fragogna Everyday Renaissance, un lavoro che ancora una volta mira a creare un sistema a parte, un “nuovo satellite nella galassia inaudita”: il libro è basato sull’apparente semplicità di accostamento di immagini ormai note del mondo dell’arte con gesti che fanno parte della quotidianità dell’universo femminile. Il confronto con il classico è di natura immediata e cattura subito l’attenzione dello spettatore. Superato il primo e più semplice livello di lettura però, emergono altre tematiche: quella della donna e del suo apparire in una società che ha sviluppato una dipendenza quasi chimica da Photoshop come fosse un pacchetto di patatine invece che un programma di fotoritocco; la componente ironica ma soprattutto autoironica, elemento questo che contraddistingue ed aggiunge una nota molto personale e anche di pregio al suo lavoro; inoltre, e insisto su questo punto, questa accessibilità al contenuto dell’opera è impreziosita e non sminuita dall’uso di strumentazioni poco costose (la macchina fotografica utilizzata non è professionale, le foto non sono ad alta risoluzione) e da una messinscena minima.

Concludendo, l’intero progetto editoriale – ideato da Barbara Fragogna e portato avanti anche grazie alla collaborazione di Claudia di Giacomo – sembra esistere per dirci che il mondo dell’arte è un universo complesso, variegato, e multiforme e che un’alternativa a un sistema forte con il quale si fatica a scendere a compromessi, esiste da sempre: basta darle voce.

di Francesca Coppola

Articolo apparso parzialmente su Exibart

L’idea di Edizioni Inaudite venne a Barbara Fragogna, artista veneta trapiantata a Berlino, ma dallo spirito mobile e itinerante, mentre stava lavorando al suo progetto Nest of Dust.

Ma iniziamo dai promordi. Cioè dalla A di Artista. Perché se ogni casa editrice incarna il suo editore, è lo sviluppo coerente della sua personalità, è la sua valigia di sogni, la sua propaggine di carta, di Barbara Fragogona non si può non parlare. Considerata la sua suscettibilità rispetto al “definire” – agli “inscatolamenti di misura standard” ai telai premontati della verbosità critica, a un sistema dell’arte che pensa sempre più di frequente ai grandi numeri, a diventare un insieme parallelo a quello Hollywoodiano –, la introduco dicendo solo che è stata curatrice al Tacheles e che appartiene a quella frangia di artisti senza vessillo, assolutamente solipsisti ed autarchici ma paradossalmente, proprio in virtù di questa sorta di ostracismo creativo, uniti tra di loro da un forte spirito di comunità e di collaborazione. Fornisco al lettore un assaggio d’artista trascrivendo in parte uno dei suoi lavori, 3rd Millennium Phenomena (cover letters) Work in progress:

«Dear Gallerist, Dearest Art Critic,

I am a female artist.

I’m a lesbian.

I have a “Social-Monarchic” attitude.

[…]

I criticize all and everything, I’ve always good issues to enucleate but I do it in an approximate way (for God’s sake, You can not expect me to be ALL-specific) and afterwards I go to bed with the enemies in order to overmaster them by my passive-aggressive manipulative strategy. […]»

Per il lavoro completo: http://barbarafragogna.weebly.com/3rd-millennium-phenomena-cover-letters.html

Per tutte le altre sue opere:http://barbarafragogna.weebly.com

Dopo questo minuscolo ritratto di Barbara Fragogna si può ora passare direttamente al progetto Edizioni Inaudite.

Il nome “Edizioni Inaudite”, riuscitissimo e accattivante, come peraltro i nomi interni delle collane da Gli Irrilevanti a Big stuff, richiama quello dell’Einaudi, caposaldo dell’Editoria italiana nel cui catalogo «ciascuno vorrebbe comparire», ma dal quale la Fragogna si distanzia per avviare un progetto totalmente inaudito, per dare voce a voci marginali, inascoltate, amiche. Altro riferimento indiscusso è Virgina Woolf: «… se si vuole fare qualcosa bisogna cercare sempre di essere autonomi. Se Virginia Woolf non avesse aperto la Hogarth Press (col marito) probabilmente non avrebbe pubblicato tutti i suoi romanzi in "tempo reale" cioè in vita... attraverso quella casa editrice, dove lei, il marito e un solo collaboratore (!) , componevano le pagine (altro che inDesign!), rilegavano e distribuivano i libri, oltre ai suoi lavori ha anche permesso ad altri scrittori e intellettuali del tempo di realizzare le proprie opere. Virginia è una delle mie pietre miliari».

Se autogestirsi è il primo obiettivo dell’artista contemporaneo, oggi diventa necessario anche mantenere caratteristiche di flessibilità e di adattabilità. E un artista che è nello stesso tempo un curatore lo sa bene. Come imprescindibile è dare voce e spazio ai propri lavori e agli artisti che condividono il medesimo percorso.

Cosa può garantire insieme l’autonomia, la flessibilità e la visibilità? Il libro d’artista. «La Casa Editrice assolve così la funzione di galleria, diventa un modo per sostenere gli artisti. Diventa cioè un progetto artistico e curatoriale».

E l’occasione nasce, come accennato all’inizio, da un personale progetto di Barbara Fragogna Nest of Dust. Il lavoro, che analizza, smitizza, ironizza, l’arte concettuale per diventare un “consapevole” lavoro di arte concettuale che a sua volta tautologicamente ironizza su se stesso, contiene già in nuce la poetica della casa editrice, come quando ad esempio evidenzia la possibilità, mediante la pubblicazione, di illuminare quei lavori che spesso per ragioni di mercato restano nelle cantine degli artisti:

«esiste un’altra faccia delle molteplici Fragogna che invece darebbe ragione ai più o meno alcuni che la chiamassero “un artista di concetto”, una teorica, una Kosuthiana. Una faccia meno nota, un lato rimasto fino ad ora in ombra, una porzione di buio che in questo libercolo noi vorremmo finalmente portare alla luce».

E in un certo senso il concetto di nido come esposto dalla Fragogna costituisce le fondamenta della Casa Editrice: «un bilancio di attrazioni e repulsioni che equilibra il senso. L’allegoria degli equilibri sociali, politici, relazionali, un passo a due e un ballo di gruppo. Nel nido si viene generati e dal nido si deve spiccare il volo. La partenza e l’arrivo, il transito, il passaggio».

La casa editrice è come un nido che protegge ed è una sorta di incubatrice energetica per gli artisti. E da cosa è costituito questo nido? Su cosa possono fare affidamento gli artisti che vi si rivolgono? Estro, contaminazione, apertura, ambizione, ironia, eleganza, serietà se vogliamo parlare dei contenuti; per ciò che concerne invece gli aspetti tecnici: un’edizione numerata, firmata, con ristampe diverse dalla prima edizione ma sempre a tiratura limitata, bassi costi di produzione, un sistema di prevendita, una percentuale più alta di quella normalmente destinata agli autori a favore degli artisti, la presentazione del libro. «Diffondere una cultura del collezionismo d’arte affrancato dall’aurea altisonante e preclusa ai più che solitamente vi si associa. Le opere pubblicate e curate da Edizioni Inaudite sono per lo più libri d’artista, dunque unici, in tiratura limitata e personalizzati in ogni esemplare, quindi vere e proprie opere d’arte». È come se il libro utilizzasse l’opera per superarla, andare oltre, per farle raggiungere un nuovo confine e guadagnarsi una nuova identità.

Così all’interno della prima collana hanno trovato posto oltre alla Fragogna: Pedro Ahner e Exilentia Exiff e presto la collana Big stuff ospiterà un volume dedicato a Giosetta Fioroni e uno a Martin Reiter.

L’ultima novità però, di prossima presentazione in Italia è il volume di Barbara Fragogna Everyday Renaissance, un lavoro che ancora una volta mira a creare un sistema a parte, un “nuovo satellite nella galassia inaudita”: il libro è basato sull’apparente semplicità di accostamento di immagini ormai note del mondo dell’arte con gesti che fanno parte della quotidianità dell’universo femminile. Il confronto con il classico è di natura immediata e cattura subito l’attenzione dello spettatore. Superato il primo e più semplice livello di lettura però, emergono altre tematiche: quella della donna e del suo apparire in una società che ha sviluppato una dipendenza quasi chimica da Photoshop come fosse un pacchetto di patatine invece che un programma di fotoritocco; la componente ironica ma soprattutto autoironica, elemento questo che contraddistingue ed aggiunge una nota molto personale e anche di pregio al suo lavoro; inoltre, e insisto su questo punto, questa accessibilità al contenuto dell’opera è impreziosita e non sminuita dall’uso di strumentazioni poco costose (la macchina fotografica utilizzata non è professionale, le foto non sono ad alta risoluzione) e da una messinscena minima.

Concludendo, l’intero progetto editoriale – ideato da Barbara Fragogna e portato avanti anche grazie alla collaborazione di Claudia di Giacomo – sembra esistere per dirci che il mondo dell’arte è un universo complesso, variegato, e multiforme e che un’alternativa a un sistema forte con il quale si fatica a scendere a compromessi, esiste da sempre: basta darle voce.

Un Rinascimento al Giorno (after Barbara Fragogna)

Pubblicato su Berlin In&Out marzo 16, 2014 da Ema Posted in Arte a Berlino, Berlino mostre, Tutta Berlino

Siete appena usciti da un Museo importante, mettiamo il caso – qui a Berlino – la Gemaeldegalerie, e davvero non riuscite a strapparvi dalle ciglia quei profili di Botticelli, quegli sguardi obliqui e misteriosi dei maestri fiamminghi (Petrus Christus o Cranach il Vecchio). Il nasone di quel mercante di Brugge eccolo spuntare sul volto di un berlinese nella U-Bahn e per un attimo, mentre vi controllate i capelli nella vetrina di Starbuck’s, vi pare – ma deve essere un’allucinazione davvero – che la vostra espressione assomigli in tutto e per tutto a quel pastore quattrocentesco assorto nel contemplare il Bambin Gesù (e non il suo ciuffo).

Ci rimangono addosso. Ci infestano. Non ci lasciano più. Madonne, mercantesse, briganti, San Sebastiani, Andromede e Re Magi. Ogni giorno, in ogni riflesso, in ogni gioco dello sguardo rispunteranno, sempre.

Perchè erano già lì.

E voi, con quella visita al Museo, li avete solo risvegliati, solleticati.

Se ne accorta da tempo anche Barbara Fragogna un’artista italiana che da anni lavora a Berlino e che davvero il suo amato Rinascimento (per non dire la sua amata Venezia) non riusciva proprio a lasciarli in dietro, oltre le Alpi. Ogni giorno, come amati spettri, tornavano a salutarla.

Certo anche in momenti estremamente personali, intimi, talvolta imbarazzanti.

Nascono così le sue “selfie” rinascimentali, un tentativo di catturare queste epifanie nel modo più profano e contemporaneo, un autoscatto da bagno!

Come lei stessa ammette nel suo progetto Everyday Renaissance c’è – oltre che tutto il suo background di artista cresciuta in mezzo all’arte veneziana – molta più Virginia Woolf che Cindy Sherman. Non si tratta infatti di “staged photography” in cui l’artista allestisce una messinscena simil-teatrale per incarnare di volta in volta quel tipo, quell’icona, quell’immagine rubata alla storia dell’arte. Piuttosto una rivelazione improvvisa che illumina, senza essere stata invocata, il secondo più improbabile della nostra esistenza quotidiana. Sei lì che ti depili le ascelle e improvvisamente la trasfigurazione: per un’istante sei una dea caduta fuori dalla tela di un Botticelli o un Rubens (a seconda della tua stazza). Siccome l’epifania è sempre improvvisa, e spesso malandrina, gli unici mezzi per catturarla devono essere loro stessi improvvisi e malandrini, come una macchinetta digitale un po’ scassata o un cellulare. Insomma, suggerisce Barbara, oggigiorno la rivelazione, l’illuminazione non sono in HD.

E ahimè neanche si annunciano con sontuosi cirrocumuli popolati di cherubini o lampi giorgioneschi o trionfi di ninfe e satiri danzanti che arredano di pampini d’uva la nostra camera da bagno.

Nel mondo di oggi non c’è più spazio per tutta questa magia, per tutta questa “aura”. Per di più siamo così sovraccaricati dalle immagini che i nostri occhi rischiano di non vederla più, nelle rare occasioni in cui si presenta…cosa? La “bellezza”

Ci vuole, e di questo Barbara è maestra, un po’ di ironia. E molta autoironia. Per ribaltare l’estrema prosaicità e noioso piattume del mondo di oggi e scovarci col sorriso smaliziato lo stesso splendore dei Santi e degli Eroi dei Bei Tempi che furono.

Perché è già tutto lì: nel gran calderone del mondo in cui ribolliamo a fuoco lento, giorno dopo giorno, sballottati dalle schiume, le bolle, le poderose rimestate. Ci siamo noi, con le nostre immaginette low quality, il profilo di facebook, la smorfia da provare mille volte allo specchio per venire bene in ogni foto e poi ci sono loro, le donne e gli uomini che i pittori immortalarono sulla tela. Sia noi, con i nostri mezzi onnipresenti democratici e un po’ rudi, sia loro, con le velature d’olio raffinatissime, il disegno di un maestro, la cornice preziosa d’oro condividiamo lo stesso smarrimento di esistere, la stessa paura di morire, lo stesso desiderio di trovare un senso in tutto questo caos.

Di loro solo pochi hanno potuto restare impressi nel per sempre.

Di noi resteranno anche fin troppi per sempre. Fin troppe immagini. Fin troppo imbarazzanti

La nostra fortuna, di uomini e donne di questi tempi novissimi, che ci è concesso di riderci su. Perchè la nostra preziosa epifania non accadrà in lunghe sedute nello studio di Da Vinci ma un giorno, per caso, mentre ci schiacciavamo un punto nero.

Le combo-fotografiche di Barbara e il suo libro in edizione limitata (e personalizzata copia per copia) saranno in mostra alla Gallery52Berlin con un’apertura speciale durante il festival d’arte di Neukoelln Frühlingserwachen il 22 e il 23 Marzo. Presente l’artista e i suoi occhi pieni di Rinascimento.

Press:

Repubblica - L'Espresso

EXIBART by Francesca Coppola

Berlin In&Out by Emanuele Crotti

Kwerfeldine by Aline Vater

Il Mitte di Valerio Bassan

UnDo

Espoarte

Lobodilattice

Okarte

ArtSpecialDay di Federica Marrella

Repubblica - L'Espresso

EXIBART by Francesca Coppola

Berlin In&Out by Emanuele Crotti

Kwerfeldine by Aline Vater

Il Mitte di Valerio Bassan

UnDo

Espoarte

Lobodilattice

Okarte

ArtSpecialDay di Federica Marrella